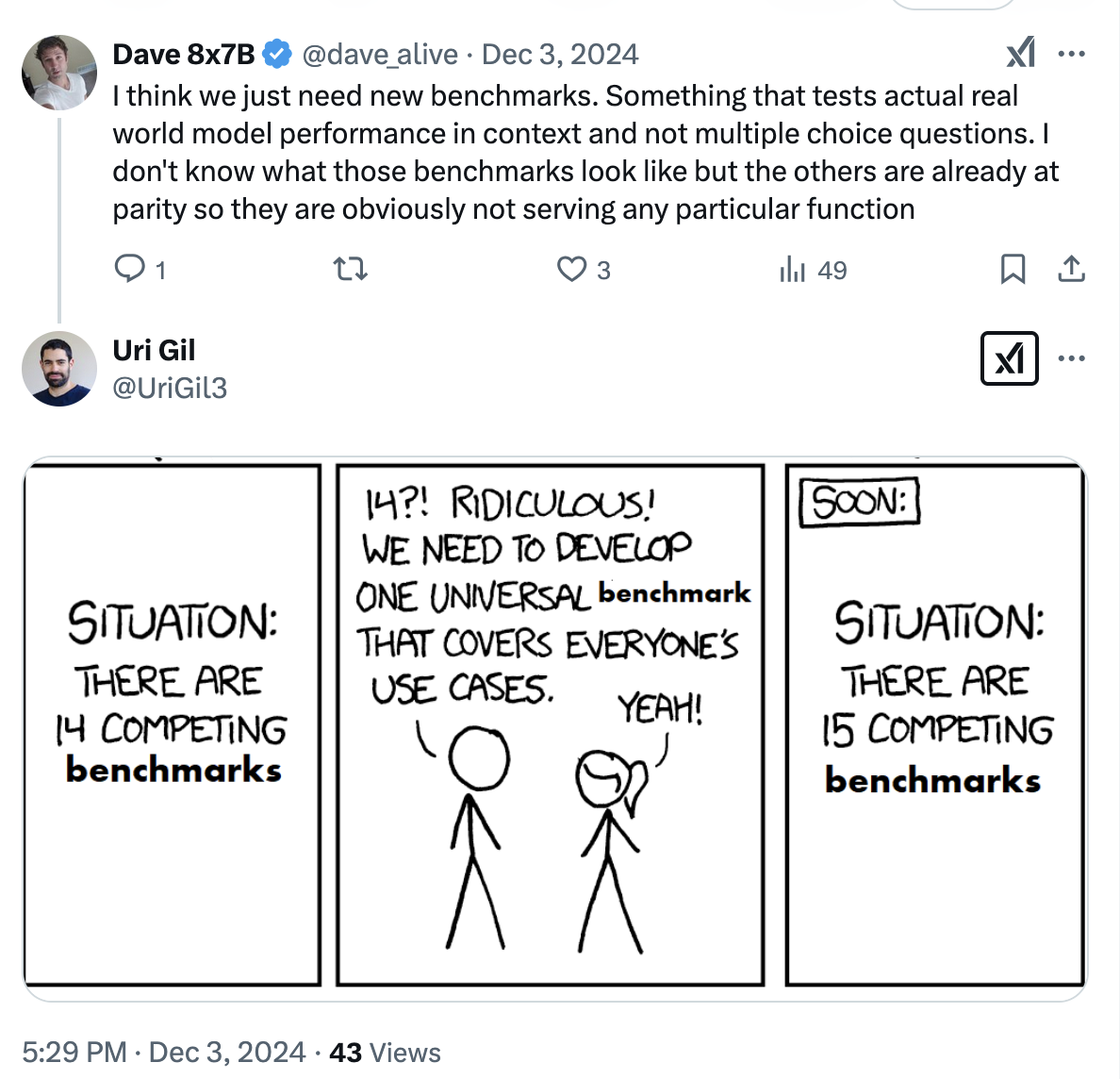

AI Benchmarks: Are We Juking the Stats?

I think I’ve seen this movie before.

I have experience in education (teaching prek, K, 4th, 6th, and college). I have got experience in tech (90’s AOL/ICQ script kiddie/webmaster turned founder). Today I’m your average generative AI user.

I care about SWE-bench rankings about as much as I cared about standardized test scores as a teacher.

Aside from quickly discerning if a model is at least GPT-4 class, benchmarks don’t tell me anything about how useful a model will be. Very similarly, standardized tests only gave me the broadest sense of a student’s knowledge and capabilities. Even then, tests suffered from false positives. Meaning a student might show proficiency on a test, but if you dig a bit beyond the surface said student might not actually have learned what the test showed. How does that happen? One way is by teaching to the test.

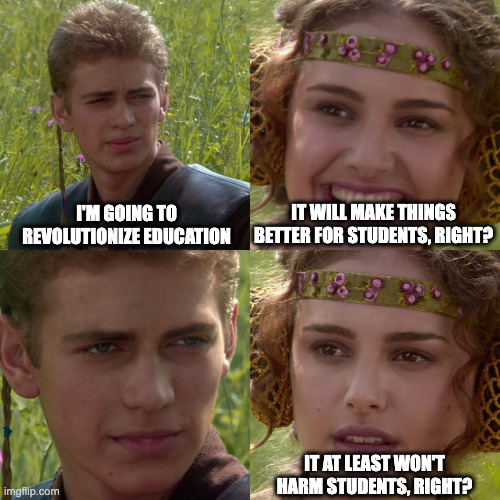

The call for better benchmarks in generative AI feels very similar to what has happened in education in America over the past 25 years. What we have done is establish a testing-industrial complex. What we haven’t done is meaningfully improve student outcomes.

So with gen AI, sure oneshotting a prompt is cool, but can Claude 3.7 or 03-mini troubleshoot my code without further making a mess of things?

Will GPT 4.5 better rework my writing than Gemini 2.0 Pro Experimental 2-05?

Does Grok have better context to understand Cognitively Guided Instruction to help me think through data collection?

Those are the kinds of things I want the current class of generative AI to help me with. Benchmarks don’t give me any insight those capabilities.

The Allure (and Illusion) of Measurement

The core idea behind both AI benchmarks and standardized tests is understandable. We want to know if AI models are getting “smarter,” just like we want to know if our students are learning.

On its face, this sounds reasonable. However, take a look at 8th grade math and literacy scores in America. They have not improved in a meaningful manner in 60 years. Yes, you read that correctly. When an article comes out about “test scores are down”, look at two things:

- The trend line dating back as far as you can see (for NAEP that’s 1973) and

- Where do the averages fall and what does that mean? When you look at both you will see next to no progress, and an average that means the majority of students are going to fail out of or just scrape by the high school math curriculum. Why does even Harvard now have a remedial math class? This is why.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Yet we continue to test the ever loving shit out of students at all levels. I remember kindergarten kids crying at the pre-test they had to take the first week of school as a part of the broader testing regime that now exists. I don’t remember making kids cry being a part of my best practices for creating a classroom environment training.

So over multiple generations we have managed to make no real gains, and create a testing-industrial complex that has unintended albeit real negative consequences.

Standardized tests are not just used to measure student learning. By extension, they’re used to measure teacher effectiveness. Phrases like “quality teachers make the difference” and “every student deserves a quality teacher” are hard to dispute. They are good sound bites! Grifters like Vivek are still out there using them today. Give me a few paragraphs and you’ll see why this is pretty stupid.

Testing has not led to quality teachers for every student. What it has led to is a very American thing. Entrenchment of an ineffective system in the name of quality and accountability. Unlike say, the Japanese, who focus on building a better system to achieve quality instead of looking to blame individuals within the system. It all feels very 1970s/1980s U.S. auto manufacturing and shows that we still haven’t learned what Deming tried to America with his Red Beads simulation.

Bill Gates, a man whose wealth and work need no introduction, bought into this American idea of teacher quality. The genesis I can’t say, but he published an article in 2010 that kicked off an initiative that married test scores and teacher evaluations to come up with teacher ratings so that we could see who the ‘quality’ teachers were. In industry, we would call this performance management. We can fast forward to 2016 and read the RAND report on the $575 million initiative the Gates Foundation launched based on this premise. The result? A resounding, expensive failure. Not only did it not improve student outcomes, in many cases, it actively harmed them.

The push for “teacher quality” was a strong siren song. So strong that it spread across the country well before the 2016 RAND report dropped. I was in the classroom during this time. It was something I bet anyone who has worked in an organization of size can relate to. Some top-down fuckery that sucks all of the oxygen out of the room, takes a ton of time, and doesn’t overlap much if at all with the real work or improvement you need to do for your job.

Now a person with an iota of experience in other industries or perhaps even someone who has picked up a book and read some history could see parallels that showed how bad of an idea this was before it even began. In 2015 I remember nodding along as I read the HBR article about performance management at Deloitte. They put some hard numbers to something that everyone seems to know, performance management is a major time suck and divorced from actual performance or employee improvement. At this exact time, education was doubling down on a heavyweight performance management system thanks to Gates and the push for “teacher quality.”

But hey, that was 2015 when things were already in full swing, and maybe Gates doesn’t read HBR.

The one that I truly don’t understand was right under Bill’s nose.

Performance Managing Microsoft Off A Cliff

“Every current and former Microsoft employee I interviewed – every one – cited stack ranking as the most destructive process inside of Microsoft” - Kurt Eichenwald

In 2012, Kurt Eichenwald published Microsoft’s Lost Decade. This article became a cultural touchstone. Why? Because it pulled back the curtain on how the tech juggernaut could whiff on the two biggest opportunities in tech (mobile and social)since the internet itself and be late to the third (cloud). Gates, who was still chairman throughout the 2000’s had a front row seat to see how Microsoft’s malevolent performance management system and its stack ranking of employees had played a huge role in the company enduring a lost decade.

For anyone who is unfamiliar with stack ranking, imagine you were a CIA agent trying to sabotage a company. You want to make the company slow and distrustful. You want to kill employee morale, motivation, and productivity. You want to make high performers hesitant to work with each other. You want to destroy collaboration. Your primary goal would be to get the company to adopt stack ranking.

This system that turned Gates’ company into an incapable sloth is what he proposed as the antidote for America’s education woes.

Bill Gates must know something I don’t to have thought bringing this type of performance management to education was a good idea after it had ravaged Microsoft. What that is though, I cannot fathom.

Goodhart’s Law: When the Measure Becomes the Target

This brings us to Goodhart’s Law. When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

An example: if you tell a factory manager her variable compensation is tied to a reduction in scrap, then she will encourage her shift managers to push every piece produced out the door. Managers may try to be judicious at first. There will be subjective calls someone has to make. They’ll inevitably green light some questionable pieces. Floor workers will see this. They’ll get looser with their QA checks. They’ll stop asking the manager and just box up every piece. New workers he come in will have no idea it is supposed to be done any other way. This one measure has just helped destroy a culture of quality within the organization. Rejected pieces returned by customers now languish in the warehouse because processing them would hit the factory manager’s scrap numbers. The system gets gamed, the company loses goodwill with customers, problems are pushed down the road, but the manager earns her variable comp.

In education, this plays out tragically. Picture this scenario which, sadly, happens too often in schools:

- Low Test Scores: A school district’s standardized test scores are low.

- State Threatens Takeover: The state warns of intervention if scores don’t improve within a set timeframe.

- Curriculum Narrows: Subjects like social studies and science get sidelined. The focus shifts almost entirely to the subjects tested – usually math and reading.

- “Teaching to the Test”: Instruction becomes laser-focused on the specific content and format of the standardized test.

- Short-Cycle Assessments (SCAs): Schools create mini-tests that mimic the big standardized test, administering them throughout the year.

- Teacher Evaluations Tied to SCAs: Teachers’ performance reviews are tied to student performance on these mini-tests.

- Teaching to the Mini-Test: The cycle intensifies, with instruction now geared towards the mini-tests, which were designed to prepare for the main test.

The result?

A miserable experience for students and teachers, a narrowed curriculum, and, often, outright cheating. It’s like that scene from The Wire when Prezbo realizes the school is “juking the stats”––manipulating the numbers without actually improving the underlying reality, just like the police force did with crime stats when he was a cop.

There are decades of documented evidence of juking the stats in education. Go back further and look into a different industry, manufacturing, and you’ll see guys like W. Edwards Deming talking about ‘tampering’ for short-term or fleeting improvements instead of doing things that actually improve the system.

And the worst part? These standardized tests, in their current form, are largely useless for improving actual teaching and learning. Analyzing scores months after the fact, when the students have moved on to the next grade, provides little to no actionable information for educators.

Formative Assessment vs. Summative Assessment: The Key Difference

Here’s where we get to a critical distinction: formative vs. summative assessment.

-

Summative Assessment: This is the “big” test at the end – the standardized test, the final exam, the AI benchmark. It’s designed to provide a summary of performance. Short-cycle assessments or quarterly mini-tests also fall into this category.

-

Formative Assessment: This is the ongoing, day-to-day assessment that happens during the learning process. It’s about understanding how students are thinking, identifying misconceptions, and adjusting instruction accordingly.

As a teacher, formative assessment is my bread and butter. It’s about having a mental model of how students progress in a subject. I concern myself with elementary students building a solid foundation in arithmetic that they can transfer to algebra and higher level mathematics. Number sense to additive reasoning. Making the big conceptual leap to multiplicative reasoning. Building an understanding of properties of operations. Using multiplicative reasoning to understand fractional reasoning, which paves the way to ratios/proportions, and then algebraic reasoning.

With this framework in mind, I’m continuously looking for and eliciting student thinking while teaching. When a student struggles, I have a good idea how to help because I understand this framework and where the student’s reasoning is within it, then what to do about it. With formative assessments I can see, understand, and give students timely, specific feedback.

For example, I have seen 4th grade students solve a four-digit subtraction problem like 4,324 - 749. They use the standard subtraction algorithm and have the correct answer on their paper. However, by observing their work and asking them to explain their process I’ve found that they understand place value up to the tens place, but struggle beyond that. A simple “right” or “wrong” answer on a standardized test would miss this crucial nuance. Teaching without this kind of formative assessment is why too many students end up building a mathematical House of Cards that is bound to fall down.

Evals vs. Benchmarks: The AI Analogy

Until recently, I had mentally bucketed AI benchmarks and evals together. I had an inkling that evals might be different, but I hadn’t done my homework. Seeing the term ‘evals’ used incorrectly like this muddied the waters. Then I listened to Karina Nguyen talking to Lenny and evals clicked for me. Evals, like formative assessments, are crucial for progress.

- Benchmarks: These look like the broad, standardized tests designed to compare different models across a range of capabilities.

- Evals: I think these are more like formative assessments. They’re customizable, task-specific evaluations used to guide the development of a particular model or feature. The kind of thing that is, and should be, a moving target.

The “Vibe” Check: When Intuition Matters

François Chollet, put it perfectly: “When a human-facing system becomes sufficiently complex, ‘vibes’ become a perfectly valid evaluation methodology.”

This might sound unscientific, but it resonates deeply with my experience as a teacher. I can often get a good sense of a student’s understanding simply by talking to them and listening to their explanations–even if they don’t get the “right” answer on a formal assessment. A student with a wrong answer may be closer to building a solid conceptual understanding than one who gets the right answer but merely has a procedure memorized.

The same applies to AI. I’ve spent good chunks of time wrestling with some code, getting nowhere with even the latest SOTA models, and realize that, despite the impressive benchmark scores, the “vibes” are off. It just doesn’t work for me in a practical, real-world setting.

The Problem with Proxies

The fundamental issue with AI benchmarks, standardized tests, and even many corporate performance evaluations, is that they rely on proxies. We can’t directly measure intelligence, learning, or the complex value of knowledge work. As in, we truly do not know how to measure these things directly. So we create these stand-ins, these metrics, that we hope will correlate with the real thing.

But these proxies often become distorted. They incentivize narrow optimization, “teaching to the test,” and gaming the system. They create a disconnect between the measured performance and the actual capability. When we forget that these proxies aren’t the real thing we want to measure, we end up with results like we have in education in America. Generations of no meaningful progress.

So, Where Does This Leave Us?

The desire for benchmarks in AI feels similar to the education system’s reliance on standardized tests. Both are:

- Time-Consuming: They suck up a lot of resources and attention.

- Prone to Perverse Incentives: They encourage optimizing for the test, not the underlying goal.

- Ultimately, Not That Useful: They provide a limited, often misleading, picture of actual capability.

When generative AI (or whatever comes next) truly reaches a level of general intelligence, we won’t need benchmarks to tell us. We’ll know.

If model providers get sidetracked by teaching to the test and optimizing for benchmarks that would make me bearish for two reasons:

-

They can’t run a tight ship. I’ve never seen a great founder, manager, or teacher focus on teaching to the test (optimizing for the short-term at the expense of the long-term). The model providers who don’t have existing businesses that are cash cows– I’m talking about the Anthropic’s and OpenAI’s, are trying to do something unprecedented. With the goal of AGI/ASI, these companies have to productize the present, while researching and developing the future. That will pull these companies in many directions, which is difficult for even the best run orgs to manage. If one of those directions ends up being benchmark optimization, that would be a waste.

-

If the goal is AGI/ASI, and you’re optimizing for short-term benchmarks, that’s telling me you don’t think you can actually get to the goal.

In the meantime, as your average AI user, vibe checks are all I need.